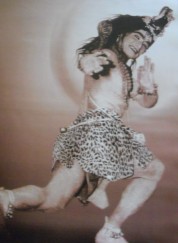

Actualmente el término “bailarín de Chhau” tiene amplias formas de entenderse puesto que los que aprenden o representan este género de danza, abordan su práctica, interpretación y su enseñanza desde diferentes ángulos, intereses y métodos. Personalmente no tomo esta denominación como algo ligero, por el contrario, es un término cargado de significados e imágenes de palacios, bosques, saltos que se suspenden en el aire, espadas, ríos, el Señor Bhairav1, heroismo y las muchas otras cosas que vienen con esta tradición de raíces profundas. De hecho creo que es un título que se llega a merecer después de comprometerse con el estilo y reafirmar este compromiso con amor, tiempo y práctica (como sucede con todas las artes). Es como un sadhana, una práctica espiritual, en la cual el ejercicio físico y el movimiento son una parte de la disciplina y los rituales, la devoción y la tradición lo complementan.

En mi camino con esta danza y en mi ávido intento de poder decir que soy “bailarina de Chhau”, he descubierto que es esencial ahondar en las raíces del lugar de origen del estilo que practico, Mayurbhanj. También que es necesario vivir su cultura y sus festividades desde adentro, particularmente el festival Chaitra Parva2. He sido afortunada de escuchar a Guruji (Guru Janmejoy Sai Babu) contándome las muchas historias del festival en tiempos antiguos: como visitaban un lugar secreto alejado del pueblo para hacer oraciones y un voto ante el dios Bhairav;

cómo danzaban toda la noche; cómo siendo uno de los principales bailarines, participaba en casi todas las danzas; cómo los mejores maestros de cada Sahi3 se retaban unos a otros; cómo los de Uttar Sahi presentaban la pieza de danza Nataraj y los de Dakhina Sahi respondían con

Mahadev; cómo la danza Navagraha se medía con Dashavatar4,; y cómo solían practicar durante meses casi que en secreto, con una integridad y una devoción inquebrantable hacia su rey, su dios y su ética guerrera. No obstante, también le escucho decir que “el festival ya no es como antes”. Este cambio inevitable comenzó desde el momento en que la realeza dejó de patrocinar el arte. Como consecuencia, la danza ha enfrentado dificultades y recaidas que la han llevado includo a ser catalogada por la UNESCO como “un arte de gran valor cultural en peligro de desaparecer” . Sin embargo, aunque es verdad que es difícil encontrar el tipo de bailarines que habían en la época de la monarquía, que mucha parte del público e incluso de los artistas lo toman como un festival folclórico5, y local y que la danza se encuentra en un nivel de calidad muy inferior al que una vez tuvo, considero que un “bailarín de Chhau” debe honrar la tradición del Chaitra Parva que ha acompañado la danza durante 200 años.

Siendo una bailarina de Chhau de Mayurbhanj pero viviendo en Delhi, percibo que la ciudad y el medio de la danza clásica demandan ciertas modificaciones y cambios en la interpretación de la danza que en mi opinión son positivos. Esto nos dirije a un periodo de transición en el que este arte toma múltiples dimensiones y desde mi punto de vista no se puede decir que es sólo una danza folclórica. ¿Acaso hay otros estilos folclóricos pasando por una situación similar? Creo que esto le sucede al Chhau y en particular al estilo de Mayurbhanj porque no es un género limitado por sólo mudras, golpes con los pies o movimientos circulares en grupo y al mismo tiempo tiene una técnica variada, codíficada e interesante que puede incluir elementos clásicos incluso como los mudras. También permite la representación de muchos temas, emociones y personajes.

Por estas razones considero firmemente que es importante que los académicos, críticos, artistas y expertos reconozcan que el Chhau es un género en expansión, que ha salido de su contexto original y que está pasando por un periodo de transición muy valioso e interesante. Sin embargo, al intentar preservar la danza y su patrimonio, no podemos desapegarnos de sus raíces locales. Más aún, no podemos permanecer ignorantes ante algunas de las cualidades intrínsicas y las tradiciones que se preservan en su tierra natal. Para tener una visión más completa de la danza, siento la necesidad de conocerlas y de ver las diferencias con las que se vive y se presenta la danza en diferentes contextos. He sido afortunada de que Guruji me inspire con las historias de cómo solía ser la danza y cómo los maestros antiguos eran casi seres con poderes sobrenaturales que podían sentarse en la rama de un árbol de un salto. Él me ha transmitido estas visiones de épocas memorables y bailarines legendarios y yo confío en que estos tiempos pueden revivir. De hecho, creo que no han muerto.

Por lo tanto, mi búsqueda actual consiste en encontrar un eslabón entre esta tradición perdida aparentemente, lo que he aprendido con Guruji, su situación presente en las áreas rurales y su interpretación modificada, contemporánea, y hasta abstracta en las grandes ciudades o los eventos clásicos y culturales. El primer paso que tomo para ir en esta dirección es viajar a su tierra de origen y vivir el Chaitra Parva desde adentro gracias a mis anfitriones de la escuela de norte y en especial a uno de sus principales artisitas, Loknath Das y Madhusmita Das y su familia con quien me hospedé durante 7 días. He estado ya tres veces en el festival. En una ocasión incluso presentamos dos danzas con el hijo de Guruji, Rakesh y otros chicos del grupo Gurukul Chhau Dance Sangam.

Fue un sueño hecho realidad el poder danzar en ese escenario tan lleno de grandes leyendas. Sin embargo esta vez fue una bendición danzar siendo parte de la escuela del norte, siguiendo su estilo como cualquier otra “chica de Baripada”. Quisiera contarles acerca de este emocionante viaje…

Quisiera contarles acerca de este emocionante viaje…

NOTAS AL PIE:

1. Bhairav es una de la formas terroríficas (grandiosas, que causan terror) del Señor Shiva. Es el padre de la danza Chhau.

2.Chaitra Parva es el festival de la primavera que se celebra el 11, 12, 13 de abril con danza Chhau .

3.Sahi se refiere a los grupos o escuelas de danza. Hay dos: Uttar Sahi – la escuela del norte y Dakhina Sahi – la escuela del sur.

4.Nataraj y Mahadev son diferentes piezas de danza que representan al dios Shiva. Navagraha es una danza acerca de los nueve planetas. Dashavatar es una pieza que representa las 10 encarnaciones del dios Vishnu.

5. Las palabras “solo una danza folclórica” no tienen la intención de ser peyorativas. Según el diccionario Merriam-Webster, se llama folclórico a una danza que “se origina como un ritual y tiene las características de un pueblo o un país y que se transmite de generación en generación.” Esto es parcialmente verdad para el Chhau porque a pesar de que hay muchos rituales ligados a él, su naturaleza no es puramente ritual. Wikipedia expone que una característica de las danzas folclóricas es que “no están destinadas o diseñadas para ser presentadas ante un público o que posteriormente pueden adaptarse para un escenario. Esto no se aplica al Chhau puesto que floreció en las cortes de los reyes de Mayurbhanj y luego la tradición del Chaitra Parva reafirma que es un arte escénico. El siguiente artículo cataloga diferentes tipos de danzas folclóricas. Según él, el Chhau sería una danza tradicional o una danza de la corte que tiene orígenes o caracteríticas folclóricas. Definitivamente agregaría “danza marcial” a la descripción, al igual que “con inlfuencias clásicas y todavía en proceso de evolución.” What is Folk Dance